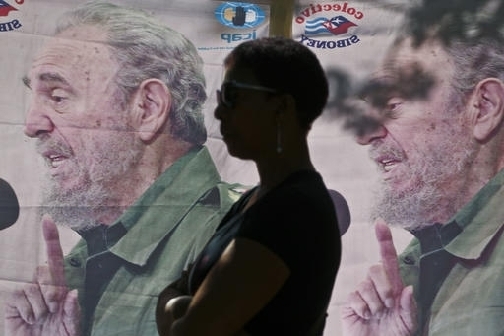

A page in Cuba’s history has turned with the death of its revolutionary leader Fidel Castro. So what happens now on the communist island?

The Caribbean nation is at a crossroads. Fidel Castro’s successor Raul Castro has said he himself plans to stand aside in 2018.

But first, emerging once and for all from his elder brother’s shadow, Raul faces the challenge of driving forward economic and political change.

Meanwhile, Cuba’s warming ties with the United States are at risk. US President-elect Donald Trump – who called Fidel a “brutal dictator” Saturday – threatened before winning the election to reverse the recent rapprochement between Havana and Washington.

Fidel Castro handed the reins of power to his younger brother a decade before his death on Friday.

But the elder Castro remained a weighty presence, publishing his “reflections” on Cuban and world affairs regularly in state media.

Officials said Fidel was still consulted on important decisions.

Raul Castro has overseen gradual economic reforms. Without Fidel in the background, change could move faster.

“With Fidel’s death, the political and economic situation will probably open up,” said Michael Shifter, president of the US research group Inter-American Dialogue. He spoke before Castro’s death.

“It will take a weight off Raul. He will not have to worry any more about contradicting his brother.”

Raul Castro has been discreetly loosening the grip of the military and state authorities on the economy since 2011, analysts say.

Reforms to the system are needed since the economy has been hit by the decline in cheap oil imports from Venezuela and falling commodity prices.

“After Fidel Castro’s death, market-oriented reforms will gain momentum, as will efforts to eliminate the more impracticable communist policies,” said Arturo Lopez Levy, a Cuba specialist at the University of Texas.

“Without Fidel’s charisma, the communist party’s positions will depend on the economic results.”

Raul Castro and US President Barack Obama restored diplomatic relations last year after half a century of hostility.

But Obama’s elected successor Trump has threatened to roll back the rapprochement if Cuba doesn’t improve its human rights record.

“All of the concessions that Barack Obama has granted the Castro regime were done through executive order, which means the next president can reverse them and that I will do unless the Castro regime meets our demands,” Trump said in September.

“Those demands will include religious and political freedom for the Cuban people and the freeing of political prisoners.”

Cuba says it refuses to be dictated to by foreign powers.

The end of the Castro era raises questions about the future of Cuba’s one-party system and who will replace the elderly generation of revolutionaries.

Raul Castro is 85 and has said he will step aside after the next Communist Party congress in 2018.

He has appointed as his number two Miguel Diaz-Canel, 56.

He is the first such high-ranking leader who is not an original member of the Castros’ revolutionary movement, which ousted former dictator Fulgencio Batista in 1959.

Now analysts foresee a struggle between hardline and more progressive members of the regime.

“The expectation of change will grow among the majority of Cubans,” Shifter said. “Fidel’s death will certainly open the door to greater conflicts and confrontations among those in power.”

“The supreme arbiter of all conflicts in Cuba will be gone,” he added of Fidel Castro.

“Raul will have much more room, but so will his political rivals.”

Moderate dissident Miriam Leyva said the death of Fidel Castro could herald the passing of a hardline sector of the old guard.

“I think there is an opportunity here to open up this society even more and progress more quickly with reforms,” she told AFP.

Since officially taking over as full president in 2008, Raul Castro has been working discreetly to “de-Fidelize” the leadership, said one Western diplomat who lived for years in Havana.

“He has spent his whole life playing the role of the regime hardliner,” said the diplomat, who asked not to be named.

“But in fact, he has long been making an effort to bring about pragmatic developments, against the ideologues that Fidel relied on.”

As for ordinary Cubans, many on the streets of Havana say they will always carry “Fidel” in their hearts. But they are looking to the future, too.

“The vast majority of Cubans feel a personal connection with Fidel,” said political scientist Rafael Hernandez, director of the Cuban magazine Temas.

That applies to “both those who support him, wholly or with reservations, and those who see him as the cause of all Cuba’s ills.”

The Western diplomat who spoke to AFP reckoned Cubans are moving on.

“Cubans buried Fidel a long time ago,” he said. “They have their faces turned to the future. For many of them, he is no more than a glorious memory.”

“The post-Fidel era started in 2006,” he added. “What matters now is what happens post-Raul.”