F) Sentencing

Whether the sentences imposed by the judge were manifestly

excessive in all the circumstances of the case (grounds 11/SC and

12/AP, KJ, AStJ).

Two preliminary applications

[42] On 9 July 2018, at the outset of the hearing of the appeal, we heard applications

by the appellants for leave to adduce fresh evidence and for the appeal to be considered

on paper.

[43] In the first application, Messrs Palmer, Jones and St John sought leave to admit

the affidavit of Miss Kymberli Whittaker, who is an attorney-at-law, and copies of the

witness statements of two jurors who were involved in the appellants’ trial. For his part,

Mr Campbell sought leave to adduce fresh evidence in the form of affidavits sworn to by

him and by Miss Kimberley Cranston on 27 April 2018 and 25 April 2018 respectively; and

the hand-written statement of Mr Lamar Chow dated 24 August 2011.

[44] After hearing the submissions of counsel on both sides, the court granted leave to

the appellants Messrs Palmer, Jones and St John to adduce as fresh evidence the affidavit

of Miss Kymberli Whittaker and the copies of the witness statements of the two jurors. In

relation to Mr Campbell’s application, leave was granted to adduce his affidavit, sworn to

on 27 April 2018, and the handwritten statement of Mr Lamar Chow dated 24 August

- The court refused the application for leave to adduce the affidavit of Miss Kimberley

Cranston sworn to on 25 April 2018.

[45] The application for the appeal to be considered on paper was also refused and the

hearing of the appeal, which was originally set for three weeks, proceeded in accordance

with a somewhat abridged timetable.

Issue A – The admissibility of the cellular phone and video evidence (exhibit

14C) (including the judge’s directions to the jury on these matters)

[46] We have already stated in broad outline the evidence upon which the prosecution

relied in this matter. As we have indicated, apart from Mr Chow’s testimony, the

prosecution relied heavily on various items of evidence which may collectively be referred

to as the “technology evidence”. In this appeal, as at the trial, counsel for the appellants

spent considerable time and effort in attempting to demonstrate that, in addition to the

fact that Mr Chow’s testimony ought not to have been relied upon, exhibit 14C ought not

to have been allowed into evidence.

The technology issues

[47] The grounds of appeal that are relevant to the technology issues are ground 10 of

Mr Campbell’s grounds of appeal and grounds 1, 2, 3, and 4 of the joint grounds of appeal

of the other appellants. These grounds complain about the integrity of the technology

evidence that was adduced by the prosecution and the judge’s handling of that evidence,

both in respect of its admission as well as his directions to the jury.

[48] Ground 10, for Mr Campbell, states:

“The [learned judge] erred when he left exhibit 14C, one of

the cellphones [sic] relied on by the prosecution, for

consideration by the jury, in circumstances where there was

direct evidence that the integrity of the said cell phone had

been significantly compromised.”

[49] The relevant grounds for the other appellants state:

Ground 1

“The Learned Trial Judge erred in admitting evidence of the

cell phones and the data therefrom which comprised one of

the fundamental strands of the case for the prosecution. The

evidence had demonstrated that these had been

compromised and contaminated to such an extent that there

was more than a reasonable doubt about their integrity as

evidence.”

Ground 2

“The Learned Trial Judge failed in his summation to adequately

deal with the issue of compromise of the cell phones and the

relating [sic] data which were admitted as exhibits. His failure

to do so was a misdirection which denied the Appellants a fair

and balanced consideration of the case against them.”

Ground 3

“The Learned Trial Judge erred in admitting video graphic [sic]

evidence which was highly prejudicial and of little, if any,

probative value. By so doing, he invited the jury to speculate

about the contents of the video and any possible linkages to

the appellants thereby compounding the prejudice and

denying them a fair trial.”

Ground 4

“The Learned Trial Judge failed to treat adequately with the

videographic evidence that he had admitted and in so failing

denied the appellants a fair and balanced consideration of

their case by the jury.”

[50] Three specific areas arise for analysis from these complaints:

a. the admissibility of exhibit 14C, given:

i. the breaks in the chain of its custody from the time that

exhibit 14C was taken from Mr Palmer to the time that

it was examined by the Detective Sergeant Patrick

Linton, the Police Computer Forensic Examiner;

ii. its admitted, unexplained use, while it was in the

custody of the police, and before it was examined by

Sergeant Linton;

iii. the discrepancies in the evidence concerning the

presence of an SD card in the instrument at the time

that it was handed over to the CFCU, where it was

examined; and

iv. the admissibility and integrity of a video clip said to

have been found on the internal memory of exhibit

14C.

b. the admissibility of a computer compact disc (CD)

(referred to hereafter as JS2) that had been prepared and

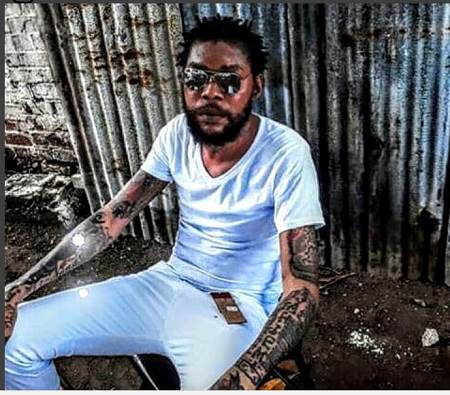

supplied to the police by the telecommunications provider,

Digicel, in respect of the use of exhibit 14C on Digicel’s

network for a period which included 16 August 2011,

given:

i. the questions relating to JS2’s identity and integrity;

and

ii. the admission that the data on JS2 was not provided

in compliance with the provisions of the ICA; and

c. the judge’s treatment of the technology evidence, in his

address to the jury.

[51] The general issue of the admission of material into evidence will be first addressed

before specifically considering the relation of that law to the admission of exhibit 14C, the

data (including the video clip) thereon, and exhibit JS2.

[52] The judge’s treatment of that evidence in his summation to the jury will then be

considered.

(a) The decision to admit material into evidence

[53] The judge was sailing in relatively uncharted waters in his quest to determine the

admissibility of exhibit 14C and its contents. There is very little in the way of learning, in

this jurisdiction, on the relevant issues. For this reason, a reference to some first principles

may prove helpful.

[54] “The cardinal rule of the law of evidence is that, subject to the exclusionary rules,

all evidence which is sufficiently relevant to the facts in issue is admissible, and all evidence

which is irrelevant or insufficiently relevant to the facts in issue should be excluded” (see

Blackstone’s Criminal Practice 2019 paragraph F1.11). The admission of evidence, the

shorthand term for the admission of material into evidence, is a question of law to be

determined by a trial judge. It is a part of every trial judge’s wider duty of ensuring that

the accused has a fair trial. Authority for the latter principles may be found in Ajodha v

The State [1982] AC 204; [1981] 2 All ER 193 and Sang v R [1980] AC 402.

[55] The general tests for the admission of material into evidence are:

a. the relevance of the material; and,

b. whether its probative value surpasses its prejudicial

effect.

Noor Mohamed v The King [1949] AC 182, is authority for those principles.

[56] Evidence is relevant if it is logically probative or disprobative of some matter which

requires proof. In DPP v Kilbourne [1973] AC 729; (1972) 57 Cr App Rep 381, Lord

Simon of Glaisdale explained the principle in finer detail. He said, in part, at page 756 of

the former report:

“Evidence is relevant if it is logically probative or disprobative

of some matter which requires proof…. It is sufficient to say,

even at the risk of etymological tautology, that relevant (i.e.,

logically probative or disprobative) evidence is evidence which

makes the matter which requires proof more or less probable.

To link logical probativeness with relevance rather than

admissibility (as was done in Sims [[1946] KB 531; (1946) 31

Cr App Rep 158]) not only is, I hope, more appropriate

conceptually, but also accords better with the explanation of

Sims given in Harris v. Director of Public Prosecutions

[1952] A.C. 694, 710. Evidence is admissible if it may be

lawfully adduced at a trial.”

[57] Noor Mohamed also explains that although material may be admissible into

evidence as being relevant, the judge, nonetheless, has a discretion to exclude it if its

prejudicial effect exceeds its probative value (see page 192). R v Flemming (1987) 86

Cr App Rep 32, [1987] Crim LR 690 is also authority for that principle.

[58] When a trial judge makes a decision to admit into evidence, or exclude from

evidence, some legally admissible material, that decision constitutes an exercise of a

discretion given to the judge. Generally, an appellate court will not lightly set aside a

decision made as a result of the exercise of discretion by a judge.

[59] Once the trial judge admits material into evidence, it is for the tribunal of fact,

which is normally a jury, to assess the weight or credibility of that evidence, if the case is

left to that tribunal. Ajodha v The State is also authority for that principle.

[60] The admissibility of an item such as exhibit 14C into evidence requires evidence

that its integrity has not been compromised. Proof of the chain of custody goes toward

demonstrating that that integrity has been preserved. There is, however, no strict

requirement to prove every link in that chain. The applicable principles were explained in

Damian Hodge v R (unreported), Court of Appeal, British Virgin Islands, HCRAP

2009/001, judgment delivered 10 November 2010. Baptiste JA dealt with them at

paragraph [12] of the judgment:

“The underlying purpose of testimony relating to the chain of

custody is to prove that the evidence which is sought to be

tendered has not been altered, compromised, contaminated,

substituted or otherwise tampered with, thus ensuring its

integrity from collection to its production in court. The law

tries to ensure the integrity of the evidence by requiring proof

of the chain of custody by the party seeking to adduce the

evidence. Proof of continuity is not a legal requirement

and gaps in continuity are not fatal to the Crown’s

case unless they raise a reasonable doubt about the

exhibit’s integrity [see R v Larsen 2001 BCSC 597 per

Romily J]. There is no specific requirement, neither is it

necessary, that every person who may have

possession during the chain of transfer be called to

give evidence of the handling of the sample while it

was in their possession. It is a question of fact for the

jury whether or not there is reason to doubt the

accuracy of DNA results because of the possibility that

security or continuity of samples was not maintained.

See R v Stafford [2009] QCA 407] at paragraph 116, where

the case of R v Butler [2009] QCA 111 is cited for that

proposition.” (Emphasis supplied)

[61] The judgment of Romily J in R v Larsen 2001 BCSC 597 is also authority for the

principle that, even if there is a gap in the continuity of custody of an item, it may still be

admitted into evidence. Those principles have been accepted in this court in Chris Brooks

v R [2012] JMCA Crim 5 and Garland Marriott v R [2012] JMCA Crim 9.

[62] It is against those basic principles that the admission of the individual items, being

the subject of the relevant grounds of this appeal, will be analysed.

(b) Exhibit 14C

[63] As has been explained above, exhibit 14C is said to have been taken from Mr

Palmer. Sergeant Linton extracted from the exhibit 14C instrument, and the cards in it, a

number of the items forming part of the technology evidence, on the prosecution’s case.

[64] Those items, however are, individually, the subject of separate aspects raised by

the grounds of appeal. For that reason, they will be considered individually. The first

outline of physical custody, however, considers exhibit 14C as a composite.

The chain of custody of exhibit 14C

[65] The judge admitted exhibit 14C, and the other telecommunication material, into

evidence after an extensive voir dire, or trial within a trial. The voir dire was conducted in

the absence of the jury. Its purpose was to determine the admissibility of material into

evidence for the jury’s consideration. The judge made his decision after hearing testimony

about how the material was identified, collected, collated and handled by the police.

[66] As has been mentioned above, there was an admission by the prosecution that

there was unexplained use of exhibit 14C while it was in the custody of the police. In

analysing the judge’s decision to admit it into evidence, it is necessary to identify the chain

of its custody, as adduced by the prosecution during the voir dire. The evidence of the

chain of its custody was given by the following witnesses:

a. Senior Superintendent Cornwall Ford (SSP Ford)

– (Vol 1, pages 227-281 of the transcript) – on 30

September 2011, took exhibit 14C from Mr Palmer and

later handed it to Corporal Abebe Pitt;

b. Corporal Abebe Pitt – (Vol 1, pages 375-386 of the

transcript) – on 3 October 2011, received exhibit 14C

from SSP Ford and later handed it to Corporal Shawn

Howard at the CFCU;

c. Corporal Shawn Howard – (Vol II, pages 815-840

of the transcript) – on 3 October 2011, received exhibit

14C from Corporal Abebe Pitt and gave it to Detective

Sergeant Patrick Linton who was also present at the

time that Corporal Howard received exhibit 14C from

Corporal Pitt;

d. Detective Sergeant Patrick Linton – (Vol II, pages

850-996, Vol III, pages 1035- 1304, 1356-1403 of the

transcript) – on 3 October 2011, received exhibit 14C

from Corporal Howard, examined it using a forensic kit

and extracted data from it and from an SD card inside

it, analysed the data extracted, which data included

text and video, prepared a CD with the material and

gave the CD to Constable Kemar Wilks;

e. Constable Kemar Wilks – (Vol III, pages 1404-1551,

1542-1551 of the transcript) – on 24 November 2011,

received the CD with data from Sergeant Linton;

created a text document of everything decipherable

from the video and audio files on the CD.

[67] The defects in the chain of custody of exhibit 14C were:

a. it was used, on 1 October 2011, to send a text

message, that is, during the time it was supposed to

have been in SSP Ford’s custody; and

b. it was used, on 9 October 2011, to make three

telephone calls, that is, during the time it was supposed

to have been in Sergeant Linton’s custody.

[68] That use of exhibit 14C was not explained by any of the prosecution witnesses.

SSP Ford was not asked any questions about it. Sergeant Linton testified that he did not

use the phone, nor did he authorise anyone to use it. He testified that he had locked it

away in a storage locker in the CFCU office, but had left the key for the locker on top of

the locker.

The data on the SD card in the instrument

[69] The SD card in the exhibit 14C instrument is important to the prosecution’s case

as it contained a number of voice notes on which the prosecution relied. The voice notes

were initially played as evidence in the voir dire. On the prosecution’s case, they are

recordings of voice messages sent by Mr Palmer. His voice in each of those voice notes

was identified by Mr Chow, both in the voir dire (see Vol IV pages 1707-1722 of the

transcript), and later, in testimony before the jury (see Vol VII pages 4000-4014 of the

transcript).

[70] On the prosecution’s case, some of those voice notes were created between 14

August 2011 at 2:37 pm and 16 August 2011 at 2:38 pm. The voice notes were played to

the court during the voir dire (see Vol III, pages 1086-1104 of the transcript). Their

contents were not fully recorded in the transcript of the voir dire, but were so recorded

when they were later recited in the presence of the jury. Essentially, the voice notes for

the period describe the following scenario:

a. Mr Palmer gave two guns, which, in the voice notes,

he calls “shoes”, to Mr Williams and Mr Chow (the

custodians) for safekeeping, which custody, he

describes as “locking” (Vol VI, page 3324 of the

transcript);

b. he received a report that the custodians could not find

the weapons (Vol VI, page 3324 of the transcript);

c. he later received information as to who had taken the

guns and how that person had gained the confidence

of, and deceived, the custodians, in order to get the

weapons (Vol VI, pages 3326 and 3329 of the

transcript);

d. he gave a deadline to the custodians for the delivery of

the weapons to him (Vol VI, page 3324 of the

transcript);

e. he stipulated that if they failed to deliver the weapons

by eight o’clock (apparently of the evening of 14

August 2011) somebody would be killed (Vol VI, pages

3327, 3330 and 3346 of the transcript);

f. he also stated that in the unlikely event that the

custodians absconded, Shawn Campbell would have to

pay for the guns (Vol VI. pages 3347 and 3348 of the

transcript).

[71] The incident, on the prosecution’s case, in which Mr Williams was killed, occurred

after 7:00 pm on 16 August 2011. The prosecution also relied on voice notes created

between 17 August at 9:57 am and 18 August 2011 at 12:13 pm. In some of those voice

notes, Mr Palmer is heard asking his correspondent about the origin of some information

that the latter had received. More particularly the voice notes for that period speak to Mr

Palmer:

a. having a tattoo put on; and

b. enquiring of his correspondent, about something that

that person has heard, and from whom; and

c. specifically wanting to know “A who him say dash dem

weh” (see Vol VI, pages 3350-3352 and Vol VII, page

4013 of the transcript).

[72] Sergeant Linton extracted other items from the SD card. These included three

specific Blackberry text message conversations (BB messages). BB messages are unique

to the Blackberry communication system. It will be recalled that the exhibit 14C instrument

is a Blackberry phone. Sergeant Linton testified that, for the purposes of the BB messages,

each Blackberry phone possesses a unique Personal Identification Number (PIN). The PIN

for the exhibit 14C instrument is 234BAE6D (see Vol III, page 1065 of the transcript). Only

the messages sent by that instrument were admitted into evidence. Those were identified

during the voir dire at Vol III, pages 1127 and 1145-1154. The judge did not admit the

replies to that instrument into evidence, because there was no evidence as to the identity of the sender of those replies. [73] The BB messages that were admitted into evidence were later read to the jury. The first BB message adduced into evidence by the prosecution is one sent from the exhibit 14C instrument to a Blackberry phone with PIN 22C4DB97. The message was sent on 19 August 2011. It says: “’tween me and you a chop we chop up di boy ‘Lizard’ fine, fine and dash him weh enuh. As Long as yuh live dem can neva find him.” (See Vol III, pages 1127 and Vol VI, pages 3402-3403 of the transcript.) [74] The second BB message, also sent on 19 August 2011, is one sent to the same Blackberry phone with PIN 22C4DB97. It says: “Well, mi tell Shawn seh H-I-E haffi buy dem back. I waan tell yuh seh mi still gi him a new 45 wha mi just get fi gwaan watch him head, and tell him seh any man missin’ dis, same treatment.” (See Vol III, page 1146 and Vol VI, page 3405 of the transcript.) [75] Another BB message, sent on 19 August 2011, to the same Blackberry phone with PIN 22C4DB97, is along the same lines as that last message. It says: “Right yah now, any man have a shoes betta take care a it like a baby weh just born.” (See Vol III, page 1148 of the transcript.) It does not appear that this message was read to the jury. [76] The next set of BB messages, which were admitted into evidence, were sent to Blackberry phone with PIN 25E00FF7. The first was sent on 14 August 2011. In it, the sender tells the receiver to instruct that the sender wants his guns by 8:00 o’clock (there was no specification as to morning or evening). The message states: “Yow, call them, [expletive] deh and tell dem seh mi want mi shoes by 8 o’clock eenuh, ban (B-A-M-M-A-N). Cause mad dawg haffi deal with dem wicked eenuh 5710021” (see Vol III, page 1150 and Vol VI, page 3407 of the transcript). By way of reference, it should be noted that Mr Clive Williams’ sister testified that his telephone number was 571-0021 (Vol I, page 100 of the transcript). [77] The prosecution then relied on a number of messages sent after 16 August 2011 from the exhibit 14C instrument to Blackberry phone with PIN 25E00FF7. The first is sent on 18 August 2011. It speaks to the relevance of Mr Chow and Mr Campbell to the sender’s thinking. It states: “Memba se a mi name (W-O-R-L-B-O-S-S), Worl’ boss, so a mi dem a go send fa, but only W-E-E, Wee or S-H-A-W-N, can sink we. So we haffi watch if police go fi dem” (see Vol III page 1150 and Vol VII page 3408 of the transcript). [78] The other BB messages sent from exhibit 14C to Blackberry phone with PIN 25E00FF7 are sent on 23 August 2011. In these messages, the sender: a. expresses surprise that the forensic investigators are acting so quickly in going to Havendale; b. warns the receiver not to talk on the phone; c. states an intention to leave the island by boat or some other conveyance; and d. expresses an alternative desire to have the receiver and other people around him. (See Vol III, pages 1152- 1154 and Vol VI, pages 3409-3410 of the transcript) [79] The third conversation using BB messages was between the exhibit 14C instrument and a Blackberry phone with PIN 22E62CE2. This conversation took place on 23 August 2011. In these messages, outlined between pages 1164 and 1195 (during the voir dire) and 3411 and 3424 (before the jury) of the transcript, the sender: a. expresses the need to leave the island fast, and asks if the receiver can assist or has any contacts that can assist; b. wants to know if a boat to the Bahamas is a possibility; c. wants to know the kind of boat that is being considered for the exercise; d. instructs the receiver not to mention his name in the transaction because he is too well known and it will be hard to keep the matter confidential; e. wonders if it is possible to fly from Jamaica “while it kinda cool” (see Vol VI, page 3417 of the transcript); f. wonders if he would be able to properly enter the Bahamas, because he was supposed to have done a show there some time before, but didn’t turn up for it; g. considers the possibility of getting in contact with a “Ras [in the Bahamas] weh keep nuff show with dancehall artist” (see Vol VI, page 3419 of the transcript); h. considers the alternatives of Cuba and Miami; i. considers the use of a ruse that entry to Cuba is needed to make a music video; j. seems to settle on using a boat and plans to leave the following morning (see Vol VI, page 3422 of the transcript); and k. considers whether he should go alone or take some people with him. [80] The defence counsel at the trial strenuously objected to the admission of that material into evidence. One of the major planks of their objection was the provenance of the SD card. There were discrepancies in the evidence in respect of the presence of the SD card in the exhibit 14C instrument. Corporal Pitt, who delivered exhibit 14C, among other cell phones, to Corporal Howard at CFCU, did not testify concerning the presence of SD cards? in any of the phones, and he was not asked any questions about such cards. He did, however, testify that he saw SIM cards in some of the instruments. [81] Corporal Howard, having received the instruments from Corporal Pitt, had the responsibility of recording in a log, that which he had received. He recorded that he received SIM cards along with some of the instruments. Those SIM cards were inside their respective instruments. At first, he testified that he had logged “the total amount of items” that he had received, including the SIM cards (see Vol II, page 827 of the transcript). When questioned about the absence of any record by him of the receipt of SD cards, he testified that it was not his “responsibility to remove or check for any” such cards (see Vol II, page 833 of the transcript). That, he said, was the responsibility of the person doing the forensic examination. [82] The first bit of evidence of the presence of an SD card in the exhibit 14C instrument was given by Sergeant Linton. He conducted the forensic examination. He said that he saw the SD card in the instrument at the time of his examination. Sergeant Linton testified that he was present and saw when Corporal Pitt handed over the instruments to Corporal Howard. He received those items from Corporal Howard. He, however, in the statement that he gave to the investigator, made no reference to seeing such a card at that time. It is only in cross-examination that he first mentioned that he saw an SD card in the exhibit 14C instrument at the time of the handover from Corporal Pitt to Corporal Howard. The video file on exhibit 14C [83] Sergeant Linton testified that in his forensic examination of the exhibit 14C instrument he found a file containing a video clip. The file was stored in the internal memory of the instrument. He said, during the voir dire, that according to the metadata (data about the data) for this file, the video was recorded on 16 August 2011 at 10:34:02 pm (Vol II, page 988 of the transcript). He said that it was recorded continuously, that is, without stopping or restarting, for two minutes and 17 seconds (Vol II, page 956 and Vol VII, page 3392 of the transcript). [84] His description of the contents of the video is given at Vol II, page 957-960 and 978-981 of the transcript. That video was played during the voir dire. It was later replayed for the jury. The video depicts a total of six males at a location. The camera taking the video is directed mainly to avoid the faces of the individuals present. Their conversation is, however, recorded. Mr Chow identified Mr Palmer’s voice as one of the voices recorded in the video (Vol VII, pages 4022-4024 of the transcript). The video also prominently depicts a pick-axe, which is said, during the course of the video, to have been swung. [85] The conversation, as described by Sergeant Linton at Vol II, pages 979-981 of the transcript, and outlined for the jury at Vol VI, pages 3396-3398, speaks to: a. whether a pick axe stick could be used to kill a man; b. holding down someone and cutting his throat; c. whether anyone in the group had a gun; d. a desire that Mr Chow should have been present to see what was happening; and, e. an instruction for Mr Campbell and Needfa Speed (the taxi driver who transported Messrs Campbell, Chow and Williams to Mr Palmer’s house), to leave. [86] Sergeant Linton testified that he took a total of 68 photographs of the frames in the video. He first spoke to them during the voir dire (see Vol II, pages 983-995 of the transcript). They were later shown to the jury during his testimony before them (Vol VI, pages 3240-3241 of the transcript). [87] The defence counsel objected to the admission of the video into evidence. Apart from the issue of its inseparable connection with the exhibit 14C instrument, learned defence counsel at the voir dire, objected on other grounds. They contended that the prosecution had not shown the video to be relevant as it: a. did not purport to identify anyone; and b. did not show any crime being committed. A further objection to the admission was that there was no proof of who had recorded the video. The other evidence on the instrument’s internal memory [88] Sergeant Linton testified that his forensic examination of exhibit 14C revealed photographic images in the phone’s internal memory. Of those photographs, three bore the same date-stamp information as was on the video recording described above, that is, 16 August 2011. Two of the three photographs, he said, were taken at 11:33 am (Vol II, page 986 of the transcript). Before the jury, he testified that they had been taken at Russell Heights, Saint Andrew (Vol VI, page 3266 of the transcript). The third photograph, he said, was taken at 3:49 pm in the Havendale area (Vol II, page 989 of the transcript). The three photographs “showed a male wearing a shirt that closely resembles that of [sic] the shirt worn in the video” (Vol II, page 962 of the transcript). The shirt in the photographs showed the entire word “TRIUMPH” written to the top front of the shirt, whereas, in the video, only the letters “PH” are visible at the top front of a similar shirt, seemingly at the end of a word (Vol II, page 960 of the transcript). [89] Mr Chow identified the man in all three photographs to be Mr Palmer (see Vol VII, pages 3991-3992 of the transcript). [90] Among the photographic images that Sergeant Linton extracted from the instrument’s internal memory is a photograph of five males. One of them is displaying a tattoo of the word “BOSS” on his left arm. That man is seen wearing a pair of black slippers with three white stripes. The photograph, from the metadata, was taken on 24 September 2011, and is said to be relevant because of a connection, on the prosecution’s case, with the video mentioned above. One of the males in the video has a similar “BOSS” tattoo on his left arm (Vol II, page 990 of the transcript), and is wearing a pair of black slippers with three white stripes, in a similar design to that in the photograph (see Vol II, page 995 of the transcript). [91] Mr Chow identified the person in the photograph with the “BOSS” tattoo as Mr St John (Vol VII, page 3999 of the transcript). The judge’s ruling on the voir dire [92] The judge made a detailed ruling in respect of the admission of the various items of technology material (Vol IV, pages 2216-2259 of the transcript). [93] In analysing the question of admission of the exhibit 14C instrument, the judge identified: a. that the instrument was important to the prosecution because of the data that was said to be on it; b. its origin as having been taken from Mr Palmer; c. the complaints about the gaps in the custody of the instrument due to its unexplained use; d. the complaints about that unexplained use; and e. that chain of custody is not a legal requirement. Those observations are recorded at Vol IV, pages 2228 to 2232 of the transcript in the judge’s ruling on the voir dire. [94] He ruled that the exhibit 14C instrument was admissible despite the complaints about the gaps in the evidence concerning the custody of the phone. He did so on the basis that proof of the chain of custody is not a legal requirement. He drew a distinction between the instrument and the data. On his analysis, the defence had not shown that there had been any tampering with the data on the instrument. Such interference with the instrument, he found, was shown to be after the events that are relevant to the case. [95] The judge having seen the video, the still photographs that had been made of the frames in the video, and the other photographs taken of Mr Palmer and of Mr Palmer’s house, found that there was sufficient evidence to indicate that the video had been recorded at Mr Palmer’s house. He is recorded at Vol IV, page 2264 of the transcript as stating some of his reasons for admitting it into evidence: “The video, as I have indicated, the Prosecution, I understand, is stating a particular place … and at a particular time, against a background where the allegations and certainly the indictment speaks to a particular date, and the thrust of the Prosecution has been to a particular time period. The main event would have occurred in that respect, the video. I see the video as a composite which includes both the audio and the visual, that were done within that framework and it is being admitted based on those facts.” [96] The judge, in wrestling with these issues, found that there was no evidence of any tampering with any of the voice notes, text messages or the video, which formed part of exhibit 14C. The judge recognised the fact that the instrument was used, while it was in the custody of the police. He noted, however, that the metadata showed that that use was after the events on which the prosecution was relying for its case against the appellants. The voice notes, text messages and video were relevant, the judge found, as: a. Mr Chow identified Mr Palmer’s voice on the voice notes and in the video; b. the video showed items, which were relevant to the case; and c. the text messages after 16 August 2011 suggested a guilty mind. [97] The judge found the various items of data on exhibit 14C, to be relevant and capable of assisting the jury in considering its decision. For those reasons, he ruled exhibit 14C admissible, with the exception of some of the voice notes thereon.