David Cameron is in Jamaica as I write. Undoubtedly the British prime minister was expecting difficult questions on his visit: from Jamaicans, about reparations for slavery, which their government demanded he discuss; from gay men back at home, about homophobic violence on the island, which they wanted him to combat. (Jamaican LGBT advocates themselves don’t necessarily want the leader of the former slave power doing a lot of shouting on their behalf; but that’s a preference of which Peter Tatchell and his comrades take no heed.) Plus there are the questions about sex with dead pigs. Yet Cameron, far more deft than his pink-cheeked Bertie Wooster mien suggests, had a distraction ready.

Once in Kingston, Cameron announced that the UK is taking £25 million (about US$ 38 million) from its foreign aid to Jamaica to finance a vital development need: a new prison. This puts Jamaica in a small, select class of nations: the UK can force prisoners to go there. It’s worth considering what this promise means. A commerce in prisoners is spreading round the world, sometimes following the almost-erased tracks of the old slave trade. Cameron’s offer reveals the hidden economics of the traffic in human bondage.

Prisoner transfer agreements — by which two countries stipulate that citizens of one who are convicted of a crime in the other can be sent back home to serve their sentence — have been around for a long time. Usually, though, they’re voluntary agreements; they require the prisoner’s consent. And many Jamaicans, Nigerians, or Albanians serving prison terms in the UK won’t consent to return to carceral systems that are overcrowded, underrresourced, and by reputation brutal. So Cameron’s administration has been trying to bully or cajol countries into agreeing to compulsory repatriation – to take their imprisoned citizens back whether they want to go or not. One difficulty has been the usual devil-in-the-details, human rights. Experts have condemned conditions in Jamaica’s prisons for failing international benchmarks: UK prisoners facing forced repatriation there could challenge it in British courts, pointing to the threat of inhuman treatment and abuse. The UK’s solution is to build Jamaica a prison that will seem up to snuff.

The government of Jamaica calls the deal a “non-binding Memorandum of Understanding” (it still needs parliament’s ratification) and makes it sound extremely nice: the goal is “to improve the conditions under which prisoners are held in Jamaica, consistent with best practice and international human rights standards, through the construction of a maximum-security prison in Jamaica.” It’s true that “international human rights standards” and “maximum-security prison” are phrases not always thought seamlessly compatible, but let that pass for now. The UK government’s statement drops the happy talk and non-binding bit, and stresses that it wants a 1500-bed facility, which will house 300-plus prisoners now serving long-term sentences in Britain, with more to come in future. “The prison is expected to be built by 2020 and from then returns will get underway,” says Downing Street. “The Prisoner Transfer Agreement is expected to save British taxpayers around £10 million a year.” Cameron added that

It is absolutely right that foreign criminals who break our laws are properly punished but this shouldn’t be at the expense of the hardworking British taxpayer. That’s why this agreement is so important. It will mean Jamaican criminals are sent back home to serve their sentences, saving the British taxpayer millions of pounds but still ensuring justice is done.

That the agreement will, in his words, “help Jamaica, by helping to provide a new prison – strengthening their criminal justice system,” seems a bit of an afterthought.

The announcement did not go down well in Jamaica. The leader of the opposition Jamaica Labour Party (JLP) wondered in parliament why this was coming out of development funds, saying that “building schools contributes much more to the growth agenda than building prisons.” The youth wing of the ruling People’s National Party (PNP) also condemned the agreement, pointing out that the UK is only funding 40% of the cost, the rest to be covered by Kingston; and that once the prison is built, the burden of keeping and rehabilitating the prisoners — which they estimate at J$ 365 million (about US$ 3.1 million) per year –would also fall on Jamaica’s treasury. (In fact, the Jamaican government claims, but the UK doesn’t mention, that Britain would give “a further £5.5 million towards the reintegration and resettlement of prisoners.” Anyway, if true, that would presumably be a one-shot offer.) The real discomfort about the deal in Jamaica, though, seems far deeper: drawing on the anger that rose in the reparations dispute over a past of slavery and oppression, a persistent demand for justice that shadowed Cameron’s tour. Symbolically, what does it mean for the British government to buy from Jamaica the right to export its prisoners? Are servitude and its machinery still commodities for sale? Comments on Jamaican newspaper articles ran like this:

So the communist are suppose to be the evil people. The Chinese build highway, Cuba build colleges and high school, the (former) slave masters return to build prison.

And I saw the same spirit in threads on the Facebook pages of Jamaican friends:

We dont need a prison from England. We can get a prison from elsewhere. England owe us more than a prison.

Its a damn shame and height of disrespect to our people….after dem slave we already, all dem can com offer us is prison … f**k dem bloodcloth off!!!!!!

(“Bloodcloth” is a Jamaican obscenity that I wouldn’t translate even if I thought I could.)

There is truth in this; prisoners are commodities. We live — so the rich remind us — on a globe that has been globalized, where everything travels and is trafficked. People travel; they become prisoners; then they travel back, under state supervision. This process is now so common that the UN has proposed a “Model Agreement on the Transfer of Foreign Prisoners“; the UN Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) offers a manual on the subject; there is a European treaty on prisoner transfers, and the EU has promulgated regulations for member states. One theme pervades these documents, that “rehabilitating” prisoners is a key motive behind transfers. The EU framework decision even phrases this as a “should” — a requirement of transfers:

Enforcement of the sentence in the executing State [that is, the country receiving the transfer] should enhance the possibility of social rehabilitation of the sentenced person. In the context of satisfying itself that the enforcement of the sentence by the executing State will serve the purpose of facilitating the social rehabilitation of the sentenced person, the competent authority of the issuing State [the one that passed the sentence] should take into account such elements as, for example, the person’s attachment to the executing State, whether he or she considers it the place of family, linguistic, cultural, social or economic and other links to the executing State.

That provision only applies to transfers among EU member countries, but it indicates a more general justification. Thus the Jamaican government promises that “The new facility will be designed and constructed with a focus on rehabilitation, which should reduce the high rates of recidivism that now occur.” Similarly, the UK prisons minister has said forced transfers “mean that these prisoners will be closer to family and friends.This helps to support prisoners’ social rehabilitation and reintegration into society.” It’s generally true that proximity to family can ease a prisoner’s re-entry after release. But of course, many Jamaican prisoners in Britain have closer family ties in Clapham than in Kingston, and are more culturally at ease in Brixton than Montego Bay. This is also “globalization”; yet the British government shows no disposition to ascertain where anybody’s “family, linguistic, cultural” and-so-on affiliations lie. The truth is, social benefits to the prisoners are the last thing on most governments’ minds in transfer policies. What matters is simple: politics and money.

And in the UK, politics means immigration. Mass mania over migration drives the whole UK political process. A poll last month showed 56% of Britons named immigration as a major concern. For years, the percent of Britons calling it the most worrying concern has been three to four times the average in other countries.

Fears of criminality always seed anti-immigrant feeling. (Think Donald Trump and those Mexican rapists.) Though capitalism mandates mobility more and more sweepingly, mobility as spectacle and spectre rouses deep terrors about stability and safety. British newspapers thunder about “foreign prisoners” constantly. You might think them less of a menace, because they’re in prison; instead, they’re vital to immigration paranoia. They’re countable; they make dread specific.And the ones already imprisoned prove all foreigners are a threat. “The number of foreign prisoners is growing and attempts to remove them are often futile”! “Foreign inmates outnumber British nationals in a UK prison for the first time”! “Every time Britain manages to deport a foreign prisoner another one takes their place in jail”! They’re making “the UK a permanent safe haven for the world’s killers, rapists, drug-dealers and other assorted scum”! In fact, while the number of foreign prisoners doubled in twenty years, so did the number of prisoners in the UK overall. You can debate whether a crime wave, harsh sentencing, or more repressive policing caused this. But the proportion of foreign prisoners has barely risen at all.

Facts don’t matter, of course. Within six months of taking office in 2010, Cameron’s coalition government tried to placate the panic, by vowing to deport the foreign prisoners: to “tear up agreements that mean convicts cannot be returned home without their consent.” It didn’t work. In fact, in Cameron’s first term the number of deportations actually fell.

Cameron needed agreements, despite the talk of tearing them up; and few countries were willing to sign them. Moreover, even criminals who had finished their sentences (presumably easier to deport, because you didn’t need a foreign prison system to agree to take them) were fighting removal in the courts, successfully.The government was reduced to creating a team of pop-psych mavens, tasked with visiting prisoners to talk them into self-deporting. “The unit uses psychological techniques known as ‘nudge theory’ to help people make better choices for themselves.”

Expert: Would you like to leave the country?

Prisoner: No.

Expert: What if I give you money?

Prisoner: How much money?

Expert: It’s a hypothetical question.

Prisoner: No.

In 2014, Dominic Raab — a young, telegenic, misogynistic, Europe-hating, ultra-right Tory back-bencher (the son of a Czech Jewish refugee, the husband of a Brazilian bride) — led a rebellion against Cameron. He proposed to grease the ejection seats for “foreign criminals,” stripping power from the courts and giving the Home Secretary final say. He boasted that “only one case every five years” would qualify to stay in Britain. The government’s response “was a mess,” one conservative pundit wrote, “first giving him a wink of encouragement only to declare his idea unworkable at the last moment.” Raab invoked the ultimate terror and temptress of the Tory right: UKIP, the extremist UK Independence Party, which every Conservative dreaded could drain their votes if they didn’t stay hard-line enough. To block his measure, Raab warned, “would be a bow-wrapped gift for UKIP.” 85 MPs joined him in revolt; Cameron only beat back the proposal with Labour’s help.

UKIP, obsessive on the subject of immigrants and crime, press-ganged everyone rightward. They demanded immediate deportation for “foreign criminals,” and damn the law. Prison Watch UK graphed their monomania:

UKIP came in third in the 2015 election, winning one seat — but almost 13% of the vote. If the Tories could lure away enough UKIP voters, they could dream of a permanent majority. In his new government, Cameron named the onetime rebel Raab an undersecretary in the Justice Ministry, with the title of “minister for human rights.”

Where does the money part come in? In the story of how Cameron pursued expulsions — and here you need to burrow back a bit. One of the first model prisoner-transfer agreements the UK reached came in 2007 under Tony Blair, who set the pattern for the Conservatives in so many ways. It happened in Libya, and it happened because Muammar Qaddafi wanted one particular prisoner back: Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, serving a life sentence in Scotland for the 1988 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103. Blair, meanwhile, wanted an oil contract for BP. In the “deal in the desert,” Tony flew to Tripoli and offered up al-Megrahi, concealing the gift under a comprehensive prisoner transfer accord — without consulting the Pan Am families, or his pet Scottish government. Qaddafi then gave the petroleum giant exclusive rights to drill in three vast blocs the size of Belgium and Kuwait together: trading territory worth billions for the inmate. Al-Megrahi was transported to Libya to live out his term; he had become the most expensive human being ever bought and sold, dearer than Diogenes or ElizabethTaylor. Petropounds lubricated the exchange. They also inaugurated Blair’s post-Downing Street career as dealmaker to dictators, a globe-trotting cross between Armand Hammer and Austin Powers.

Subsequent prisoner transfer agreements have been similarly mercenary. But the cash has flowed the other way. Downing Street says that, in addition to Jamaica, “Compulsory transfer agreements are also in place with Albania, Nigeria, Somaliland, Rwanda, and Libya.” Except for Libya (where a once-respectable GDP has plummeted since the Royal Air Force’s little 2011 incursion) these are all poor countries. (Nigeria has oil but the per-capita GDP is barely one-fourth of what Libya’s was in 2007.) Cameron persuaded a paltry four impoverished nations to take their prisoners back, by paying them.

With some countries (particularly those where tiny prisoner contingents are involved) the effect can be achieved by dangling small amounts of apparently unrelated aid or benefits before the recipient government. With Nigeria, according to the Nigerian press, it involved a £3 million “annual fund to rehabilitate prisons.” This money wasn’t mentioned in the UK government’s announcement of the Nigerian deal (though the Daily Mail had indignantly warned of it long before); in fact, at least two years of payoffs, to facilitate Abuja’s acceptance of voluntary transfers, appear to have preceded the compulsory-transfer signing. The funding thus seems devoid of the monitoring mechanisms usual to bilateral aid programs. Given Nigeria’s high place on the global corruption index, it would be anybody’s guess where the cash wound up.

Map of Somali piracy, 2005-2010, showing major trade routes, Somalia (Somaliland is roughly the northwest panhandle of the country), and Seychelles

Triangular trade: Map of Somali piracy, 2005-2010, showing major trade routes, Somalia (Somaliland is roughly the northwest panhandle of the country), and (lower left) Seychelles

Somaliland stands out on that list, because it isn’t a nation. It’s a breakaway region claiming independence from fragmented Somalia. The formerly British part of a country stitched together from British and Italian colonies, Somaliland runs a competent PR machine in London, apparently with enough cash to rent some would-be politicians. (UKIP is a great supporter of Somaliland’s contested statehood, as is Peter Tatchell.) But clearly it could use more. Its place on the roster has a complex backstory that unveils the colonial essence of the prisoner-transfer enterprise.

The deal traces back to Britain’s concern over piracy off Somalia’s coasts. That piracy, made immortal by a Tom Hanks movie, affected plenty of developed economies moving goods through the Suez Canal — by early this decade annual losses exceeded US$ 6 billion. But it took place in international waters, and none of the surrounding states were eager to prosecute captured pirates. Britain helped prevail on the Seychelles — a tiny island nation that was a UK colony from 1810 till 1976 — to take on the job.

Seychelles mainly contributed its name and territory; in “a scheme funded by the Foreign Office and the United Nations,” to the tune of £9 million from Cameron’s government, Britain then controlled the trials and the jails. The UK sent its own prosecutors. One struck the proper colonial note in a BBC interview, describing Somali captives as a “cheerful and reasonably intelligent lot.” The UK also built a maximum security prison — a “paradise” behind “15-ft high razor wire” that housed 100 Somalis by 2013 — and contributed its own warden. There were too many Somali convicts coming out of the courts for the facility to hold, however. So Britain also brokered a compulsory transfer agreement between Seychelles and Somaliland for the latter to absorb the overflow.

Will Thurbin, former governor of an Isle of Wight prison, poses at Montagne Posse Prison in Seychelles with his dog Lucy, while Somali prisoners behind razor wire look on. Photo by Kate Holt for the Daily Mail

Will Thurbin, former governor of an Isle of Wight prison, poses at Montagne Posse Prison in Seychelles with his dog Lucy, while Somali prisoners behind razor wire look on. Photo by Kate Holt for the Daily Mail

Somaliland thus opened a “pirate prison,” with £1 million from the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (and presumably more from Britain); by 2012 it held 313 Somalis. Prisoners were shunted from shore to shore like backgammon counters. (A Brit working for UNODC in Seychelles joked to the BBC “that most Somalis are happy to be sent [to Somaliland] to escape the prison diet of rice and tuna.” In Somaliland, prisoners told the Guardian that “The food here is not good. We get rice, tomatoes and only a little bit of meat. In Seychelles the food was better.”)

Familiar colonial problems dogged the whole process. The British prosecutors knew no Somali nor Arabic; they couldn’t understand what the people they sent to prison were saying. “We didn’t have lawyers and we didn’t know the language,” a Somali inmate told the Guardian about his Seychelles trial, claiming he was merely fishing when gunboats arrested him. He got 10 years. A British barrister complained of “a marked inequality of resources between the prosecution and defence which was capable of producing injustice.” Moreover, flouting their basic rights, prisoners sent to Somaliland were stripped of any ability to appeal their convictions in Seychelles. But the point was, some pirates wound up behind bars, and piracy declined, and oil flowed through the Gulf of Aden. Seychelles was, of course, an old slave colony, familiar with involuntary transits. And Somaliland was desperate for official acknowledgement, and willing to sell itself as a prison camp to get it. (The head of Somaliland’s Anti-Piracy Taskforce “said the funding, and Somaliland’s increasing usefulness in the fight against piracy, would help the enclave’s bid for international recognition of its independence.”) Exploiting these two weak and dependent territories, Britain built a regional economy of prisoner transfers around its own needs. It was like a miniscule Indian Ocean version of the Atlantic triangular trade.

WIth all this going on elsewhere in the world, Jamaica knew there was money in the prisoner-transfer business, and drove a hard bargain. The deal Cameron announced had been in the works since at least 2007; but it’s easy to infer that, as Kingston saw other countries profiting, its own price went up. Britain paid to import chained humans to its territories for several centuries. There’s a certain justice that, as the whirligig of capital brings round its revenges, it must now pay to export them. Of course, for the humans in question, “justice” may not be the right word.

* * * * * * * *

One thing must be clear. Bilateral aid to improve developing countries’ prison systems should be a good, needed thing. People who claim aid must focus on “nice” projects like schools or hospitals ignore the fact that prisoners have needs and rights — rights that governments disdain and deny. Suggestions (by the PNP’s youth league, for instance) that foreign donors should leave prisons alone adumbrate a dangerous nationalist antagonism to human rights altogether.

But whom will Britain’s Jamaica project help? To begin with, you have to note that the UK’s attitudes toward foreign prisons are hopelessly discordant. When it’s a question of a British citizen incarcerated abroad, those places are primitive hells — “terrifyingly alien,” a barrister wrote of Jamaican jails; “the cells are the size of a typical one-car garage.” When it’s a question of shipping a non-citizen back to his homeland’s prisons, those receptacles are fine, fine. Torture? What torture? As Dominic Raab said, it’s horribly wrong when “We have innocent British citizens being carted off … to face flawed justice systems or gruesome jails abroad. But we can’t send foreign gangsters back home.” In other words, surprise! — Britons worry about prisons abroad when it suits their interests.

There are deep human rights problems in Jamaica’s prisons. The country has an incarceration rate about the same as England and Wales (a third of Russia’s, a quarter of the United States’); but the system is teeming and ill-maintained.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights declared in 2012 that “Detention and prison conditions in Jamaica are generally very poor primarily due to overcrowding, poor sanitary conditions, and lack of sufficient medical care.” A 2010 investigation by the UN special rapporteur on torture determined the country’s two main prisons “are not suitable for modern correctional purposes, including rehabilitation and re-socialization.”

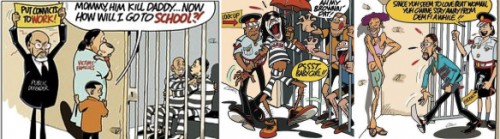

But here’s the problem. Every country wants a prison system because every country thinks it’s the answer: to crime, to excess population, to immorality or poverty. But nobody wants to pay for it it. It’s true in the US, in the UK, and in Jamaica. There is no constituency in Jamaica for spending tax money to improve prisons, or aid money for that matter. (The current government has dabbled with bringing in private, for-profit prison corporations, but couldn’t find a taker.) Part of popular mythology around prisons in Jamaica is that they’re too luxurious, not harsh or primitive enough, lenient leisure clubs that drain men of manhood and leave them batty bwoys. Real abuses like rape that make imprisonment unendurable instead become the spoor of pampering. Clovis, the notoriously homophobic cartoonist for the Jamaica Observer, rams home the point:

(It’s sobering to compare this with the UN expert’s report: “Homosexuals detained at St. Catherine and Tower Street correctional centres were held in the ‘vulnerable persons unit’ as a protective measure. However, their separation led to a loss of privileges of a punitive character, such as work and recreation, including the use of the library and playing field. In the security section in the Tower Street centre, detainees were locked up in dark, solitary cells without a toilet or water, and had nobody to call for help.”)

It’s improbable that the UK money will do anything to change overall prison conditions in Jamaica, much less the beliefs and policies that produce them. It’s not meant to. At best, Cameron’s bargain will create a two-tier prison system: lucky UK exports will enjoy the cutting-edge prison’s comparative comforts, along with privileged dons and barons who can pay for it, while everyone else swelters in the old inferno. And this is fine with Britain. Given the UK’s desperation to slough off unwanted inmates, there’s little chance they’ll seriously inspect even the new facility’s standards. It’s fine with Jamaica too. Already the government is talking about this not as a rights issue, but a real estate one: the possible superannuation of one old penitentiary means that “Downtown Kingston will have the opportunity for a large redevelopment on the 30 acres of waterfront land now occupied by the prison,” the National Security Ministry told the press. “A similar opportunity for redevelopment would be provided in Spanish Town.”

This is a story about commodities. It’s a very contemporary one. When people lose their freedom and their rights, they become objects; but under triumphant capitalism, an object can only be a commodity, must bear a price. These days, the unfree are destined to be bought and sold.

The UK is building a market in prisoners; it exports the problem of prison to other states, and pays them to take it. The idea of the price of individual prisoners permeates the discourse. “The average annual cost of a prison place in the UK is £25,900,” Downing Street declares. The Daily Mail envisions a more upscale product, like free-range chickens, and pegs them at “around £40,000 a year.” The aggregate numbers are what counts in interstate relations — the “£25 million a year to keep 850 foreign prisoners behind bars,” the “£35 million every year” spent “locking up Poles” who strayed our way — but the single prisoner remains the nominal unit of exchange, like the lone dollar or pound whose abstract value in its minute oscillations can set unimaginably vast capital flows in motion.

Yet this is the nativist language of an economy in recession. The UK’s reasoning is clear: if we have to spend that much on prisoners, which we don’t want to, let’s spend it on our own, not foreigners. “Deporting foreign criminals would free up prison places,” says a UKIP politician, letting us abuse and humiliate more of our own kind. There’s no reason the logic should stop there, though. Already the UK is figuring out ways to scrap the formality of a trial; Cameron’s government has come up with “Operation Nexus,” to simplify deporting foreigners charged with crimes but not convicted. And isn’t there a deeply buried message: Look. We would deport our own citizens if we could. Can a mere ID deter ostracism and eviction? With a West desperate to export crime and get rid of immigrants, why is birthright belonging more than a friable, disposable defense? Donald Trump already wants to scrap it. If the UK could find a penal colony, a Botany Bay, to take its suspect and unwanted nationals, how long would it cling to them over legal sentimentalities? As non-citizens become criminals, an insidious mirroring begins; the possibility — the fissure — of turning criminals into non-citizens opened, after September 11. The United States now can kill its own nationals without trial. It can pry in their doings as if they all were foreign spies. Correspondingly, zones of statelessness are starting to spring up, like weeds in the cracks of a formerly seamless planet. Guantanamo was the first, but not the last. Somaliland “enjoys relative peace and stability,” writes Reuters, parroting its Cameronland informants, “and analysts hope it might be a good site for more incarcerations in the future.” There you go — “peace and stability” now simply mark out promising lands for prisons, the way a geologist looks at a glittering slope of schist and sees oil. But the analysts don’t come to Somaliland for the quiet. Its draw is that it’s not a state; human rights treaties and duties don’t apply. Because such places are, in a global sense, lawless, states can set up laboratories there to make their own law. It’s not so much the fact that such small, silent interstices are appearing, in a world that used to talk of legality and freedom. It’s the fear that in those interspersed crevices and ruptures, our terrifying future is being born.

No one likes to talk about the links between slavery and prisons, but they are real. Both Michelle Alexander and Loïc Wacquant show how the modern prison in America grew in response to the formal abolition of involuntary servitude; the reality and constant threat of incarceration forged new psychological as well as legal shackles around an ostensibly liberated population. The prison shared — and shares — many features with the model case of human slavery in the 20th century, the Nazi concentration camp. Here’s something I read recently that chilled me.

In the American South after the Civil War black convict labourers, leased out for dangerous, back-breaking work and subject to summary punishment and execution, sometimes had a mortality rate as high as 50 per cent in certain states. … Mortality among the tiny minority of white prisoners was around 2 per cent.

A 50% mortality rate for the imprisoned is roughly the rate for Hitler’s work camps (as opposed to the pure death camps, like Sobibór or Treblinka). The Gulag’s death toll, for example, was only half that. The enslavement of the human being; his reduction to a rightsless cipher; her extermination once her economic use was exhausted — these are extreme cases, absolutely not typical of all incarceration. But they’re possibilities inextricably latent in the modern prison: because buried under the prison is the slave camp.

Chain-gang prisoners working on a railroad, Asheville, NC, undated photo (late 19th or early 20th century)

Chain-gang prisoners working on a railroad, Asheville, NC, undated photo (late 19th or early 20th century)

What we’re seeing now is twofold. Imprisonment is no longer a reserve away from the economy where the unproductive can be shunted; it’s completely economized. And the prison economy is going international. This traffic in chained bodies is growing. It resuscitates the authority structures of colonial slavery with new legal forms, purposes, and names. It’s frightening to see even a few of the old slave-trade routes revived like grass-grown oxen tracks, running from Britain to Jamaica or the Bight of Benin, from the Indian Ocean islands to the East African coast — though sometimes the shackled people are borne in directions opposite to the map’s faded arrows.

Hilary Beckles, the chair of Caricom’s Reparations Committee (and vice-chancellor of the University of the West Indies) published an open letter before Cameron’s arrival in Jamaica. It cited how the prime minister’s own clan had profited from Britain’s slave economy; in the 19th century, Cameron’s distant relations owned 202 slaves in Jamaica. Beckles wrote:

You owe it to us as you return here to communicate a commitment to reparatory justice that will enable your nation to play its part in cleaning up this monumental mess of Empire. We ask not for handouts or any such acts of indecent submission. We merely ask that you acknowledge responsibility for your share of this situation and move to contribute in a joint programme of rehabilitation and renewal.

Cameron rejected all such calls. Jamaica, he told its parliament, should “move on from this painful legacy and continue to build for the future.”

But how? It’s Cameron whose state policies summon the ghosts of the traffic in human lives. The only future that lies that way is inhuman.