Jennings, Thomas L. (1791- 1856)

Back to Online Encyclopedia Index

Thomas L. Jennings was the first black man to receive a patent. The patent was awarded on March 3, 1821 (US Patent 3306x) for his discovery of a process called dry-scouring which was the forerunner of today’s modern dry-cleaning. Jennings was born free in New York City, New York in 1791. In his early 20s he became a tailor but then opened a dry cleaning business in the city. While running his business Jennings developed dry-scouring.

The patent to Jennings generated considerable controversy during this period. Slaves at this time could not patent their own inventions; their effort was the property of their master. This regulation dated back to the US patent laws of 1793. The regulation was based on the legal presumption that “the master is the owner of the fruits of the labor of the slave both manual and intellectual.” Patent courts also held that slaves were not citizens and therefore could not own rights to their inventions. In 1861 patent rights were finally extended to slaves.

Thomas Jennings, however, was a free man and thus was able to gain exclusive rights to his invention and profit from it. Jennings was a passionate abolitionist who used the income from his invention to free the rest of his family from slavery and fund abolitionist causes. He served as assistant secretary of the First Annual Convention of the People of Color which met in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in June 1831.

Thomas Jennings died in New York City in 1856.

homas Jennings stands in history as a noteworthy figure for being the first Black person to ever receive a patent, but his life should serve as an example of what was, and what could have been, for Black people in the earliest years of the United States.

Thomas Jennings was born in 1791 and worked in a number of jobs before focusing on what would become his chosen career… as a tailor. Jennings’ skills were so admired that people near and far came to him to alter or custom-tailor items of clothing for them. Eventually, Jennings reputation grew such that he was able to open his own store on Church street which grew into one of the largest clothing stores in New York City.

Jennings, of course, found that many of his customers were dismayed when their clothing became soiled, and because of the material used, were unable to use conventional means to clean them. Conventional methods would often ruin the fabric, leaving the person to either continue wearing the items in their soiled condition or to simply discard them. While this would have provided a boon to his business through increased sales, Jennings also hated to see the items, which he worked so hard to create, thrown away. He thus set out experimenting with different solutions and cleaning agents, testing them on various fabrics until he found the right combination to effectively treat and clean them. He called his method “dry-scouring” and it is the process that we now refer to as dry-cleaning.

In 1820, Jennings applied for a patent for his dry-scouring process. In light of the times, he was fortunate that he was a free man, born in the United States, and thus an American citizen. Under the United States patent laws of 1793 (and later, as revised in 1836) a person must sign an oath or declaration stating that they were a citizen of the United States. While there were, apparently, provisions through which a slave could enjoy patent protection, the ability of a slave to seek out, receive and defend a patent was unlikely. Later, in 1958, the patent office changed the laws, stating that since slaves were not citizens, they could not hold a patent. Furthermore, the court (in the famous case Oscar Stuart vs. Ned case) said that the slave owner, not being the true inventor could not apply for a patent either. In true irony, when many of the southern states seceded from the Union to form the Confederate States of America, CSA President Jefferson Davis signed into law legislation permitting slaves to hold patents. For Thomas Jennings, none of this mattered because as a free man, not only was he able to receive a patent in 1821, but he was also able to utilize it for his financial gain. In fact, he made a fortune.

What makes Jennings noteworthy is not just that he was an entrepreneur or that he received a patent, or even the fact that he became very wealthy. What is noteworthy is that he took a vast amount of the proceeds of his business and poured it into abolitionist activities throughout the Northeast. In fact, in 1831, he became the assistant secretary for the First Annual Convention of the People of Color in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He passed this sense of self-worth to his daughter Elizabeth, who was forced off of a public bus in New York City which she riding to go to church. Because of her father’s prominence and wealth, she was able to obtain the best legal representation and hired the law firm of Culver, Parker, and Arthur to sue the bus company and was represented in court by a young attorney named Chester Arthur, who would go on to become the 21st President of the United States. Ms. Jennings would ultimately win her case in front of the Brooklyn Circuit Court in 1855.

Thomas Jennings died in 1859 and will go down in history as the first Black person to obtain a patent, but he should rather be seen as an example of a citizen who made the best of his life and sought to use his good fortune to make life better for those around him.

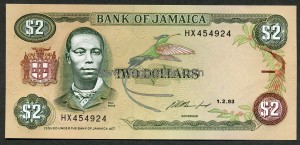

weren’t we taught this guy was Paul Bogle?

So this man left from clear a NY reach a JA fi say him name Paul Bogle now this is very confusing n disturbing

So who is Paul Bogle. #Confused

As far as I know is paul bogle on the bill this dont mek sense.

So infuriated, disappointed and disgusted. Efforts should be made to discover who was responsible for this, and to find #The Real Paul Bogle.

http://jamaica-gleaner.com/article/lead-stories/20181009/stop-asking-it-paul-bogle The Final Answer

Why couldn’t it be that this post has the wrong picture? Why are we so quick to say that we are in error?