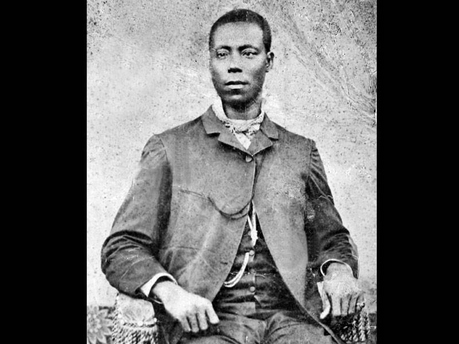

Paul Bogle – Defender of the people

Kevin O’Brien Chang, Contributor

BY 1865, the American civil war and a severe drought had dramatically increased food costs in Jamaica, while collapsing sugar prices had cut estate wages and made work scarce.

In January, Edward Underhill wrote a letter describing ‘the extreme poverty of the people’ who had to ‘steal or starve’. He criticised the Jamaican legislature for high tax levels and denying blacks political rights.

‘Underhill’ meetings of persons wishing to change the system sprang up across the island. The people of St Ann even addressed a petition to Queen Victoria, complaining of hardships and asking to be rented Crown land at low rates. The colonial office responded with ‘The Queen’s Advice’ telling labourers that, “it is from their own industry … that they must look for an improvement in their condition”.

In August 1865, St Thomas vestry (assembly) member George William Gordon attacked Governor John Eyre for sanctioning ‘everything done by the higher class to the oppression of the negroes’ and reportedly raised the spectre of Haiti. Gordon’s political agent in Stony Gut was native Baptist preacher Paul Bogle. Chosen in an open-air meeting to lay the complaints of the people before the governor, Bogle led a delegation march 80 kilometres to the then national capital Spanish Town. But they were refused a hearing.

Bogle began to hold secret meetings and drill his men. He visited the Hayfield Maroons to enlist their support, as the Maroons were greatly feared for their violence in quelling unrest. They later claimed to have offered him no encouragement, but Bogle said they had agreed to help him in a quarrel he expected to have with the bukra. “The Maroons is our back,” he said.

Skirmish with police

On October 7, Bogle and a group of men were involved in a skirmish with police at court, and arrest warrants were issued. But when the police went to apprehend Bogle, about 300 men disarmed them. Bogle complained in a petition to the governor that, “an outrageous assault was committed upon us by the policemen … . We therefore call upon your Excellency for protection, seeing we are Her Majesty’s loyal subjects, which protection if refused, we will be compelled to put our shoulders to the wheel, as we have been imposed for a period of 27 years with due obeisance to the laws of our Queen and country, and we can no longer endure the same.”

On October 11, 1865, several hundred black persons led by Bogle marched into Morant Bay. They confronted the white and brown militia protecting the St Thomas vestry, and fighting erupted. By nightfall the crowd had killed 18 people and wounded 31 others, while seven members of the crowd died. Disturbances spread across the parish and martial law was declared. By the time it ended a month later, 29 whites and browns had been killed, and nearly 500 mostly black persons executed in retaliation.

Bogle insisted he was not rebelling against the Queen, and merely wanted ‘fresh gentlemen from England’. But whites saw the St Thomas outbreak as a massive conspiracy of blacks intent on taking over the island. It was ruthlessly put down with the brutal help of the Maroons.

Gordon was identified with the rebellion and arrested. He denied involvement, and though seriously ill at the time, was convicted and hung on October 23. Also on October 23, the Maroons captured Paul Bogle, who was also hung the next day.

The harshness of the suppression led to the Jamaica Royal Commission enquiry in England. This praised Eyre for acting promptly, concluding there was no general conspiracy, but that given the ‘general excitement and discontent’, the rebellion might have spread to other parishes if not quickly suppressed. It condemned him for prolonging the period of martial law, for the injustice of Gordon’s trial, and for the barbarous retributions. It attributed the uprising to demand for land, and a breakdown in the justice system.

Trying to avoid the rule of an emerging black majority, the National Assembly dissolved itself and voted for Crown colony government. So for the next 18 years, Jamaica was ruled by a non-elected governor-appointed legislative council.

Modern Jamaica is often dated from 1866, when the new governor, Sir John Peter Grant, began restructuring the administrative apparatus. New courts were established, a new police force was created, and the Church of England was disestablished in Jamaica. Road and irrigation systems were improved, more money was spent on health and education, and in 1872 the capital was moved from Spanish Town to Kingston.

The new system of governance was also freer of nepotism and local favouritism, which made civil servants harder to bribe. So in the end Gordon and Bogle did get a good measure of what they bravely fought and died for – fair and competent government.

Kevin O’Brien Chang is managing director of Fontana Pharmacy and author of ‘Jamaica Fi Real: Beauty, Vibes and Culture’. Send feedback to [email protected]. www.kevinobrienchang.co