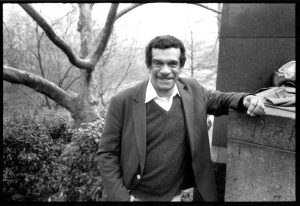

Derek Walcott, whose intricately metaphorical poetry captured the physical beauty of the Caribbean, the harsh legacy of colonialism and the complexities of living and writing in two cultural worlds, bringing him a Nobel Prize in Literature, died early Friday morning at his home near Gros Islet in St. Lucia. He was 87.

His death was confirmed by his publisher, Farrar, Straus and Giroux. No cause was given, but he had been in poor health for some time, the publisher said.

Mr. Walcott’s expansive universe revolved around a tiny sun, the island of St. Lucia. Its opulent vegetation, blinding white beaches and tangled multicultural heritage inspired, in its most famous literary son, an ambitious body of work that seemingly embraced every poetic form, from the short lyric to the epic.

With the publication of the collection “In a Green Night” in 1962, critics and poets, Robert Lowell among them, leapt to recognize a powerful new voice in Caribbean literature and to praise the sheer musicality of Mr. Walcott’s verse, the immediacy of its visual images, its profound sense of place.

He had first attracted attention on St. Lucia with a book of poems that he published himself as a teenager. Early on, he showed a remarkable ear for the music of English — heard in the poets whose work he absorbed in his Anglocentric education and on the lips of his fellow St. Lucians — and a painter’s eye for the particulars of the local landscape: its beaches and clouds; its turtles, crabs and tropical fish; the sparkling expanse of the Caribbean.

In the poem “Islands,” from the collection “In a Green Night,” he wrote:

I seek,

As climate seeks its style, to write

Verse crisp as sand, clear as sunlight,

Cold as the curled wave, ordinary

As a tumbler of island water.

He told The Economist in 1990: “The sea is always present. It’s always visible. All the roads lead to it. I consider the sound of the sea to be part of my body. And if you say in patois, ‘The boats are coming back,’ the beat of that line, its metrical space, has to do with the sound and rhythm of the sea itself.”

There was nothing shy about Mr. Walcott’s poetic voice. It demanded to be heard, in all its sensuous immediacy and historical complexity.

“I come from a place that likes grandeur; it likes large gestures; it is not inhibited by flourish; it is a rhetorical society; it is a society of physical performance; it is a society of style,” he told The Paris Review in 1985. “I grew up in a place in which if you learned poetry, you shouted it out. Boys would scream it out and perform it and do it and flourish it. If you wanted to approximate that thunder or that power of speech, it couldn’t be done by a little modest voice in which you muttered something to someone else.”

Mr. Walcott’s art developed and expanded in works like “The Castaway,” “The Gulf” and “Another Life,” a 4,000-line inquiry into his life and surroundings, published in 1973. The Caribbean poet George Lamming called it “the history of an imagination.”

Mr. Walcott quickly won recognition as one of the finest poets writing in English and as an enormously ambitious artist — ambitious for himself, his art and his people.

He had a sense of the Caribbean’s grandeur that inspired him to write “Omeros,” a transposed Homeric epic of more than 300 pages, published in 1990, with humble fishermen and a taxi driver standing in for the heroes of ancient Greece.

Two years later, he was awarded the Nobel Prize. The prize committee cited him for “a poetic oeuvre of great luminosity, sustained by a historical vision, the outcome of a multicultural commitment.”

It continued: “In his literary works Walcott has laid a course for his own cultural environment, but through them he speaks to each and every one of us. In him, West Indian culture has found its great poet.”

As a poet, Mr. Walcott plumbed the paradoxes of identity intrinsic to his situation. He was a mixed-race poet living on a British-ruled island whose people spoke French-based Creole or English.

In “A Far Cry From Africa,” included in “In a Green Night” — his first poetry collection to be published outside St. Lucia — he wrote:

Where shall I turn, divided to the vein?

I who have cursed

The drunken officer of British rule, how choose

Between this Africa and the English tongue I love?

Betray them both, or give back what they give?

Derek Alton Walcott was born on Jan. 23, 1930, in Castries, a port city on the island of St. Lucia. His father, Warwick, a schoolteacher and watercolorist, died when he was an infant, and he was raised by his schoolteacher mother, the former Alix Maarlin.

Both his parents, like many St. Lucians, were the products of racially mixed marriages. Derek was raised as a Methodist, which made him an exception on St. Lucia, a largely Roman Catholic island, and at his Catholic secondary school, St. Mary’s College.

One of the greatest to ever do this! We’ve lost a legend, a true son of soil.Rest in Power Mr . Derek Walcott!

Metty, you hear that Peter Abrahams Murderer claims he and the 90 odd year old wheelchair bound man had a gay “special” relationship. Damn raas lying, murderer a tarnish the man’s name in death.

Wonder if him really using that to help his defense? hope it backfire and dem add more years to him sentence for that

Also thought he was the helper’s husband

I wouldnt be surprised a lot of them will do anything for money . Wicked

RIP Derek Walcott legendary Nobel prize winner. I remember using his material in sixth form.